EPD release by KARSTEN PACKEISER (EPD) from 07.03.2025

There are many methods for recycling construction debris. However, in war zones where resources are scarce, these methods are often not feasible. A civil engineer from Mainz had an idea for turning rubble into new building blocks with minimal technical effort.

A Vision Born Over Coffee

Mainz (epd) – It all started at the coffee table in the Mainz-based architecture firm where Alfons Schwiderski is one of the two partners. A young Syrian was employed there as a trainee draftsman, and conversations often touched on the situation in his war-torn homeland. One day, a bold plan emerged: “One day, we will rebuild Aleppo.”

After years of conflict, many Syrian cities have been reduced to rubble. In Ukraine, the government in Kyiv estimates that around 330,000 buildings have been destroyed due to fighting and missile attacks. In the east, entire cities lie in ruins. The situation in Gaza is even more dire, with months of relentless Israeli bombardment creating apocalyptic conditions. Across all these regions, the question remains: How can reconstruction be organized?

Even in Germany, the recycling of construction debris is an important issue—primarily for environmental and climate protection reasons, says Schwiderski. “We still build a lot with concrete, which is one of the most environmentally harmful materials.” In war zones, however, the challenge is different: high-quality building materials are often unavailable. After World War II, Germany itself had to reuse debris out of sheer necessity.

Turning War Rubble into Bricks

Technologies for forming stones from crushed debris have existed for a long time. Typically, about 30% cement is added as a binding agent, explains Schwiderski. However, in crisis regions and poorer countries, even cement is an expensive and scarce resource. He has now partnered with a non-governmental organization (NGO) in Gaza with the goal of eventually replacing cement entirely with ash. Developments in this direction are already underway, both locally and in Germany.

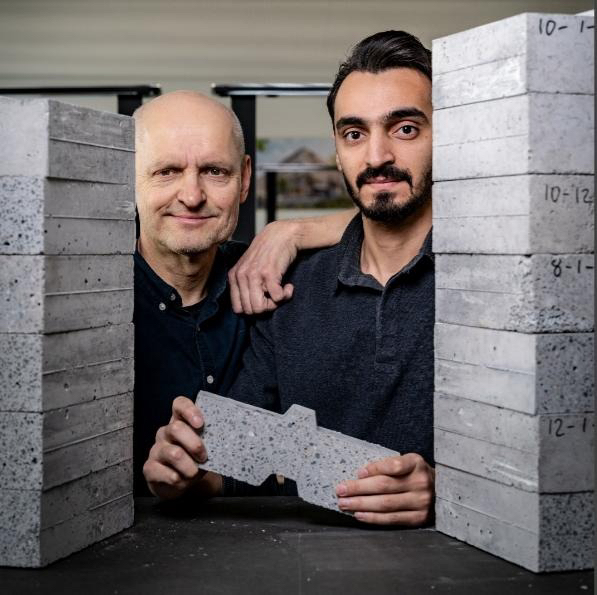

Schwiderski’s specially designed bricks weigh 11.3 kilograms and are shaped to interlock. In principle, even multi-story buildings could be constructed with them—potentially even without mortar. “Any small business with a machine could produce its own bricks.” Simple stone crushers operated by laborers are sufficient for production.

Together with his brother, Schwiderski has patented a wooden building block and even constructed a small demonstration building with it. While this material could be used in Ukraine’s reconstruction, it is less suitable for Gaza or Syria. “In the Middle East, houses are not built from wood,” he notes. However, he does not intend to patent his war rubble bricks—he wants as many people as possible to use them. “My real goal is to produce the bricks locally in partnership with a joint company,” he says. “This is not a charity project.”

A Concept Supported by Aid Organizations

The idea of using locally available materials for reconstruction is also embraced by major aid organizations. The Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) in Eschborn, for example, recently supported the construction of a school cafeteria in Niger using locally produced bricks. “In the Sahel, GIZ builds with simple materials under challenging conditions,” a spokesperson explains. Political instability, limited transport infrastructure, and a lack of functional vehicles make access to construction sites difficult. As a result, local villagers constructed the building using materials they produced themselves.

Schwiderski has already reached out to GIZ and established contacts with an NGO in Gaza. West of Mainz, he has also purchased land that once housed an old brick factory and was later used as a scrapyard. Here, he plans to set up production for his bricks. Even the factory hall itself will be built using his own construction materials.

By relying on simple, locally sourced materials, Schwiderski’s approach offers a practical, low-tech solution for rebuilding war-torn areas—giving communities a chance to reconstruct their homes with resources they can produce themselves.